Introduction

Materials and Methods

Experimental design

Sample collection and analysis

Statistical analysis

Results

The effect of probiotics as spraying agent in slurry

The effect of probiotics as spraying agent in pig house

Discussion

Conclusion

Introduction

The emission of harmful gases from intensive farming is a significant higher and becomes. one of the reasons for the increase in global temperatures and the greenhouse effect (Marszałek et al., 2018). With the increased degree of intensive farming, nowadays the accumulation of large quantities of faecal slurry in pig sheds produce more harmful gases which in turn pollute the environment (Wang et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2010; Jeong and Kim, 2014; Calvet et al., 2017). Studies have shown that animal husbandry emissions account for 14.5% of total emissions, making it the second-highest contributor (Giraldi-Díaz et al., 2021; Twine, 2021). Furthermore, the noxious gases generated in pigsties can adversely impact the health and growth of pigs (Michiels et al., 2015). Additionally, improper handling of faecal slurry can be hazardous to public health (Sun et al., 2021).

Among many probiotic bacteria, Bacillus has been reported to show the greatest promise as a live-fed microorganism due to their inherent ability to withstand severe environmental stress and change during storage and handling (Upadhaya et al., 2019). Available research shows that Bacillus spp. is beneficial in growth performance and decrease gas emmision (Sureshkumar et al., 2022). According to a 2013 study by Bellot et al. (2013) bedding of animals (horses, guinea pigs, and cows) with Bacillus strains of probiotics reduced the unpleasant odor of animal feces.

The decomposition of proteins in faecal slurry is the primary cause of the production of noxious gases. Studies have shown that feeding pigs probiotics can reduce harmful gas emissions. Recently, our laboratory has discovered that applying probiotics to faecal slurry through spraying reveal more effective strategy to reduce harmful emissions. However, they use only one particular strain probiotic. Herein, we focus to use mixed probiotic (Bacillus subtilis and Lactobacillus plantarum) and examine how effectively these strains could help to supress the odor from pig slurry and barn.

Materials and Methods

Experimental design

Two finishing pig (n = 150 head per room) rooms were selected at first. One house was named as control (CON) and probiotic (PRO) for a period of 3 weeks all pigs were allowed to fed corn-soybean meal diet (formulated according to NRC, 2012) and free access to water. The CON room was sprayed with saline water, while PRO room was sprayed with mixed probiotics (Bacillus subtilis (1.0 × 107 cfu·g-1) and Bacillus licheniformis (1.0 × 107 cfu·g-1) in a 1 : 1 mixture). Spraying was done twice a day at 8 am and 8 pm. The underfloor cesspit is 0.45 m deep and has an area of 22.8 m2. Control of room temperature at 18 - 21℃ and humidity at 60% through environmental control settings.

Sample collection and analysis

Faecal slurry samples were collected from eight evenly spaced points within the pig house cesspools on days 0, 7, 14 and 21, and stored in 2.6 L plastic airtight container and incubated at room temperature for 24 h before determining the harmful gas concentration. Finally, NH3, H2S, methyl mercaptans, acetic acid, and CO2 contents were determined using a multi-gas detector (Multi-RAE Lite, RAE Systems, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data obtained were analysed using the t-test procedure in SAS 9.3 (SAS, 2014). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The effect of probiotics as spraying agent in slurry

Fig. 1 showed that the effect of microbial spraying agent in slurry. The application of mixed probiotics through spraying significantly mitigated H2S emission from the slurry on day 7, 14 and 21 (p < 0.05). Moreover, spraying a mixture of probiotics significantly reduced the elevated concentrations of methyl mercaptans, acetic acid, and CO2 in slurry on day 7, 14 and 21 (p < 0.05).

The effect of probiotics as spraying agent in pig house

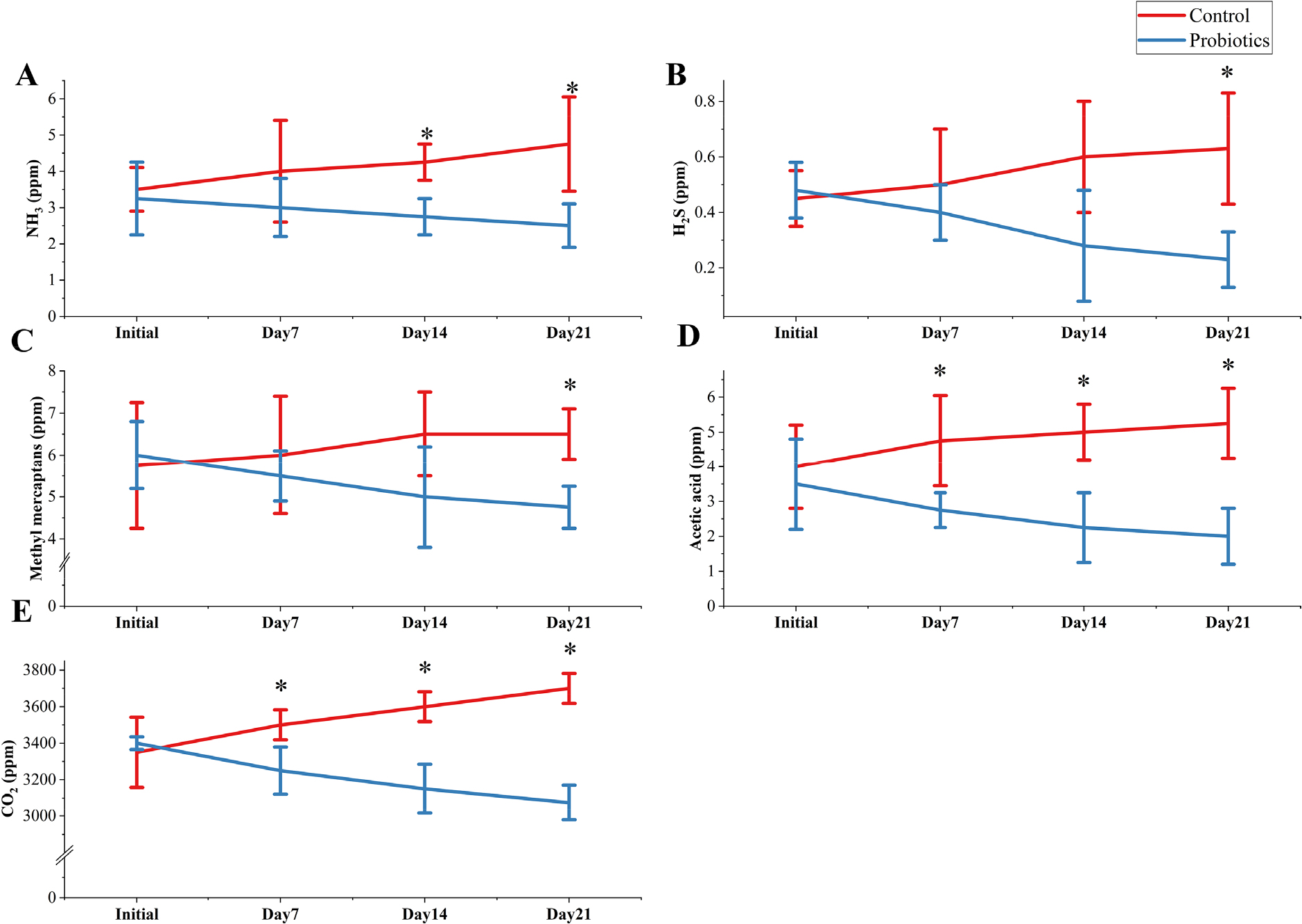

Fig. 2 demonstrate a decreasing trend in gas emissions in the pig house after probiotic spraying. Airborne concentrations of NH3 were significantly reduced on days 14 and 24, while H2S and methyl mercaptans were significantly reduced on day 21. Additionally, acetic acid and CO2 concentrations were significantly reduced on days 7, 14, and 21 in the pig house (p < 0.05).

Discussion

NH3 in piggeries is primarily produced from urea in contact with urease (Van Kempen, 2001). H2S is a chemically unstable reducing agent that oxidises easily and produces toxic substances when burned. NH3 and H2S are both harmful gases with unpleasant odours (Habeeb et al., 2018). Excessive emissions of these gases can cause respiratory illness and acidification of ecosystems (Wu et al., 2020). Methyl mercaptan has a disagreeable odour that can cause discomfort, although it does not have any apparent pathological characteristics when inhaled (Luttrell and Bobo, 2015). Excessive emissions of acetic acid can cause environmental acidification and strongly irritate and damage the human respiratory tract (Ernstgård et al., 2006). Although carbon dioxide is a colourless and odourless gas, excessive emissions can cause nitrogen and oxygen toxicity in animals, as well as contribute to the greenhouse effect (Sawyer, 1972; Langford, 2005). Odours from farms are primarily produced by the microbiological transformation of organic matter from the gastrointestinal tracts of animals, manure pits, and floors (Hamon et al., 2012). Therefore, adding probiotics to reduce the concentration of harmful gas-producing microorganisms could be a potential method for decreasing gas emissions. Several studies have demonstrated this fact. Bacillus, Lactobacillus, and Yeast can reduce harmful emissions from pig manure. The addition of probiotics to the diet has been demonstrated to significantly reduce the excretion of nitrogen in faeces, thereby reducing the production of noxious gases. This is evidenced by studies which have shown that odorous compounds are produced mainly due to microbial fermentation of undigested proteins excreted from the gastrointestinal tract through anaerobic fermentation. Furthermore, certain probiotics are employed in the composting of manure with the objective of accelerating the fermentation process. Consequently, the present study sought to ascertain the impact of incorporating probiotics directly into the slurry on the emission of noxious gases from the slurry. Although previous studies have demonstrated that the application of probiotics to manure slurry can result in a reduction in the production of harmful gases, Nevertheless, the efficacy of employing distinct probiotic strains remains to be determined (Kim et al., 2014; Muhizi and Kim, 2022).

The breakdown of urea nitrogen in urine by urease-producing bacteria such as Bacteriodes, Bifidobacteria, and Proteus is followed by its conversion to NH3 and CO2 by contact with bacteria in faeces. Consequently, the reduction of ammonia levels and the inhibition of bacteria that produce harmful gases represent crucial elements in the reduction of harmful emissions. The results of this study showed that spraying mixed Bacillus probiotics in manure slurry reduced the concentration of harmful gases in manure slurry (Muhizi and Kim, 2022). It could be a difference in the concentration of probiotics used as well as differences in house conditions. In addition, the use of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens alone on faecal slurry after treatment in the fermenter reduced the production of noxious gases from the slurry, which is consistent with the results of this study (Kim et al., 2014). In addition, this study was conducted in an actual farming environment where probiotic treatment was carried out, allowing for a more realistic collection of results of probiotic treatment of faecal slurry. We can see from the trend of the graphic curve that spraying a mixture of probiotics reduces more the amount of H2S, as well as the concentration of methyl mercaptans, acetic acid and CO2 in the faecal slurry. It can be concluded that the levels of harmful gases in the unsprayed mixed probiotic group showed an increasing trend with time, while the spraying of the mixed probiotic significantly reduced the levels of harmful gases in the air and showed a decreasing trend. Although the results of this study demonstrated similar trends to those observed in previous studies, the reduction in harmful gases was not as pronounced. Previous studies have demonstrated that Bacillus subtilis produces antimicrobials that reduce the number of ammonia-producing bacteria in faeces (Lisboa et al., 2006). Furthermore, Bacillus spp. sensors produce organic acids with the effect of lowering the pH of the faecal slurry, thereby reducing nitrogen deamination (Wang et al., 2009). It is widely accepted that Bacillus spp. have the ability to hydrolyse proteins, as they produce a multitude of hydrolases to degrade a diverse range of substrates. Furthermore, Bacillus spp. has been demonstrated to be an effective agent for the removal of H2S (Arakawa et al., 2000). This may be the reason why a reduction in harmful emissions was observed in this study.

In summary, the gradual reduction of harmful gases in the air may be due to the fact that the spraying of mixed probiotics in the faecal slurry is effective in reducing the content of harmful gases in the slurry, which leads to a lower degree of volatilisation due to a lower concentration.

Conclusion

Spraying a 1 : 1 mixture of Bacillus subtilis (1.0 × 107 cfu·g-1) and Bacillus licheniformis (1.0 × 107 cfu·g-1) at a concentration of 500 g per tonne in the slurry of the pig house would be better option to reduce the gas harmful from pig slurry and barn. We believe that our result would provide a novel insight to use probiotic as spraying agent to improve the air quality and reduce the environmental pollution.